Last time, we talked about hiragana for a while. This time, we’ll be taking a closer look at katakana, the second of the three scripts in Japanese — before you ask, kanji is probably a bit more than one article can cover. This is going to be more about origins, quirks of usage and so on rather than anything that’s useful straight away, though, like before: This article is for history and interesting facts, we can be practical some other day.

Katakana has all the characters you’d be used to, plus ヱ and ヰ, which are respectively we (ゑ) and wi (ゐ). They’re archaic and, nowadays, only seen in the Ainu language and some Ryukyu languages (as well as mainland Japanese fiction that’s trying a bit too hard). Functionally, it’s almost exactly like hiragana. The obvious question, then, is why it exists, and what it’s actually used for that’s different at all: What’s the difference between hiragana and katakana anyway?

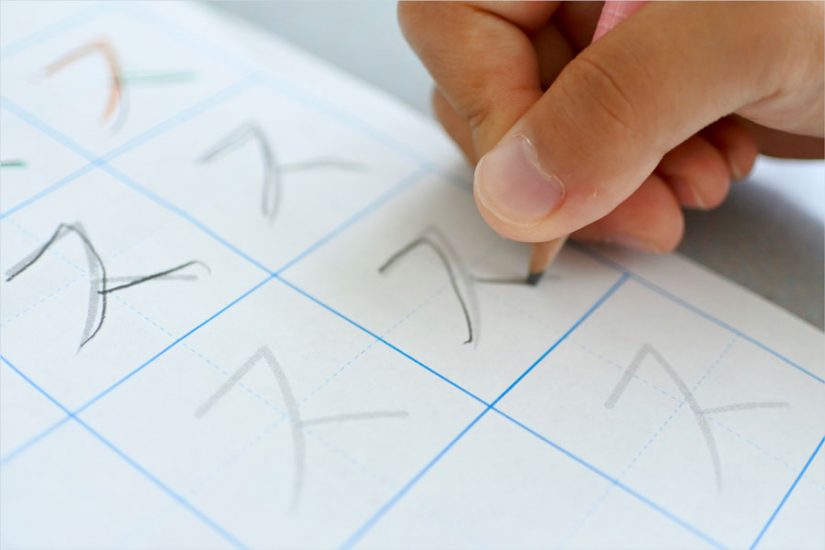

Katakana’s origins (formerly otokode or ‘man’s hand’) can be uncovered easily by looking at it. It’s basically radicals from kanji turned into letters as shorthand, which then became their own phonetic letters, often inspired by the kanji they once came from — for example, カ and 加 are both ‘ka’. This was done in large part by monks because it turns out writing all your kanji by hand takes more time than anybody has. The less blocky hiragana was developed separately in part, and in other part based on this, mostly by court women. More than that would just repeat the last article, so let’s move on and cover something new.

Katakana has a few uses, which — like all grammar and language — expands a bit when it enters fiction, and writers realise grammar is just a toy that makes funny noises when you prod it the right way.

Practically, it has something that’s gradually creeping into hiragana use, but mostly stays at home: The ー character, a line that extends the previous syllable. ホーム rather than ほおむ, for example. However, keeping up the trend with which script you use, you will definitely see things written the second way on purpose sometimes.

The first and most obvious one is that katakana is the loanword script. This can be applied to every word Japan borrows from another language, but most commonly it’s for Latin languages: Portuguese, Dutch, English and so on. There are some examples to the contrary (for example, カルビ is taken from Korean), it’s just a bit less common. Similarly, foreign names, with an obvious exception (even then, not totally guaranteed) for Chinese names, are rendered in katakana. Generally, more modern Chinese terms, especially those that can’t easily be converted to kanji, will take the form of katakana.

In addition, it can be used for some company names, scientific terms, onomatopoeia (this is one of the most consistent uses, and even then it’s not complete), old computer code, and for emphasis. That is, katakana might be used the same way as italics, although putting dots above the letters or to their sides is more common in my experience.It can also be used as a replacement for complex kanji, and for some reason is preferred over hiragana for that.

Finally, in fiction, it can often be used not just for foreign language speakers (to mark a heavy accent or broken Japanese), but also for any character who’s meant to sound ‘off’, or unusual in some way: Robots, monsters with inhuman voices, and so on. For the latter point, a semi-common example in English novels might be a character who speaks entirely in small upper case letters.

You might notice a trend here. When do you use katakana? When do you use hiragana? At these points and in these situations, usually, maybe, unless you’re really not feeling it that day. A lot of this is wishy-washy because they’re not actually hard grammatical rules, although some people might give you a funny look for flouting it. The thing is, most of this is stylistic choices and tone-based picks all the way down, and as such, there aren’t any hard rules, just general trends and going with what feels right in the moment. For a writer, this is probably nice. For anyone trying to make sense of it, this might be frustrating. On the other hand, learning katakana outside of that is just recognising the characters and mapping it to the hiragana you know, so it won’t take much work!

As a more modern trend, some names are written with only katakana and/or hiragana, and no kanji. However, if anything the reverse is more common: Ordinary kanji given exotic readings. When you do see pure hiragana or katakana names, the idea is to make it easy to read so that it feels simple and approachable; more commonly seen with women’s names, but sometimes men’s names too.

Conversely, among older generations — at this point anyone growing up in 1930s and earlier — some only had katakana names for reasons that had more to do with not being able to read kanji in the first place. Unfortunately, there were also women who only had katakana names out of the perception that ‘important’ kanji names should be reserved for sons; thankfully, that hasn’t happened in a long while.

Lastly, katakana sees two lesser-known uses that I think are important to bring up: It sees semi-official use (alongside some Latin alphabet; there are two equally used versions) as the Ainu alphabet, a language which is sadly barely preserved at the moment, but I think that makes bringing it up all the more worthwhile. Similarly, Ryukyuan language has no official script, but kanji, hiragana and katakana are all used to render it, despite it being mutually unintelligible with mainland Japanese.

That’s it for katakana for now: A simple enough script with lots of rules on when and how to use it, and none of those rules are actually real in practice (but that’s the last thing I get to make fun of while writing in English). One day, we might take a look at kanji as well.