Before video games, there were tabletop roleplaying games. Before that, there were ‘wargames’, board games based on strategic combat, sort of like a very distant ancestor of modern X-COM, or any game with ‘tactics’ in the name. Before that, people were very bored but didn’t really have the time to do much about it.

For anyone who’s not familiar with the term, tabletop roleplaying games (or as they’re sometimes called in Japan, tabletalk games) are the original form of RPGs. Players each play the role of a character (usually acting in character for most of the time), sit around a table and go through a story organised by a sort of combination referee and writer, referred to as the GM or DM (Game Master or Dungeon Master). The main selling point is the total freedom of options; you’re telling a story together, there’s no computer to limit what your characters can or can’t do. The main downside is that you can already guess how easy it is to consistently get five or so adults with a couple spare hours in the same place.

If you’re not familiar with the term, you’ve probably at least heard of Dungeons & Dragons, which is definitely the most popular example, if not necessarily what the medium has to look like (in the same way that not all video games have much in common with Overwatch, for example).

A lot of what we take for granted in video games comes from RPGs. From moral alignments to inventories to the very idea of classes, persistent character progression, an ongoing plot (arguably) or a party of characters, an absolutely enormous number of concepts come back to tabletop RPGs, and especially D&D. This isn’t even counting actual video game adaptations of tabletop systems, such as a few Warhammer games (fewer than you’d expect; most only borrow the settings), or the late 90 s to mid-2000 s flood of computer RPGs that outright used D&D systems, such as Baldur’s Gate. The latter has more or less fallen out of favour; its successor can be seen in games like Pillars of Eternity or Dragon Age, presumably because they can hammer the systems into a shape that fits video games more that way, and don’t have to pay for licenses.

What’s less obvious is that this has had its fair share of effect on Japanese video games as well; quite impressive, considering that Japan was on the other side of the world from most of the early growth of tabletop, and nobody really bothered to localise this sort of thing to Japanese for a long while. Since we only have so much space to talk about this, let’s limit the scope a bit, and look at some examples of how it influenced early video games.

That’s not to say that’s all it influenced in Japan; it kicked off a (very small and quiet) Japanese tabletop industry too, and while I don’t really watch any shows or read comics, I’ve heard there’s one called Records of Lodoss War that’s essentially an adaptation of the author’s D&D games (the exact same origin story as Dragonlance in the west, funnily enough). For a niche hobby, nobody tried to introduce to Japan, it made a splash. Today, though, we’re focusing on the games.

When it comes to Japanese games, the first name most people think of is probably Final Fantasy. You wouldn’t guess it now, but the early games drew very heavily on tabletop. The typical party in D&D was a rogue (a thief), a fighter, a cleric (that is, a priest and healer), and a wizard. The first Final Fantasy’s assumed composition copied this almost entirely, with the small change of rebranding the latter two into, respectively, White Mage and Black Mage.

Another big one: Ever wondered why FF1 doesn’t use the ubiquitous mana/magic point system (mana, by the way, being a term borrowed from Hawaiian mythology), and instead makes you prepare spells in advance, which you then use a limited number of times per day? That’s how it worked in D&D, and since FF came about from someone at the office going “what if we made D&D but for televisions?”, that’s what we have. D&D got the idea from how magic works in Jack Vance’s Dying Earth series of novels, and the entire medium has had the baggage of ‘Vancian magic’ ever since.

Welcome to game design history.It gets strange, and eventually, most of it wraps back to D&D, which in turn mostly traces to Tolkien and 70 s pulp authors.

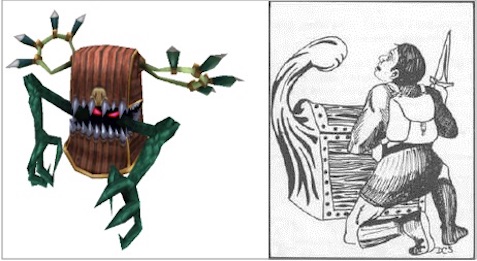

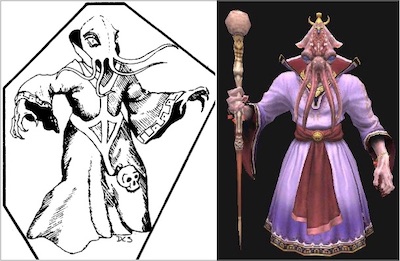

Final Fantasy 2’s (somewhat infamous) system of practicing everything to improve it, like a slightly messier version of what the Elder Scrolls series is known for? Also from tabletop, albeit not D&D; that has more to do with Runequest and the like. Oh, and then you have the repeated use of original D&D monsters, such as mimics (yes, that’s a D&D invention), mind flayers and displacer beasts.

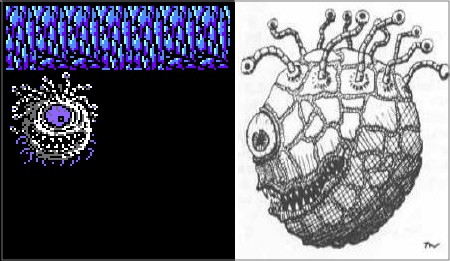

In order, you can see comparisons for mimics, displacer beasts to coeurls, mind flayers to same, and (for a bit, although they didn’t do it after FF1) beholders, all D&D inventions. I’m not completely sure how they got away with this one. Of course, mimics are something you’ll see in most RPGs by now. I’ve tried to stick to older editions of D&D for comparisons to make the point, but not so old that the art starts to look like newspaper cartoons.

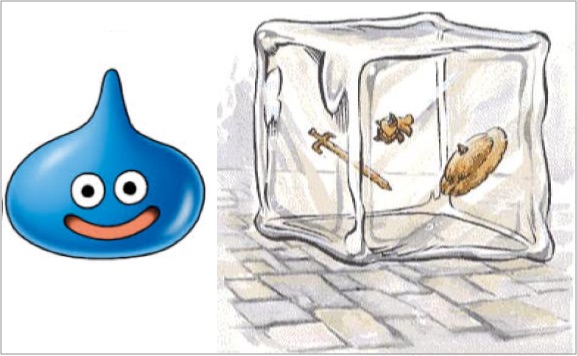

But let’s move away from that. Dragon Quest (or as it’s sometimes known in the west, Dragon Warrior) has its homages at the earliest stages as well: The iconic slime monster, and the entire concept of a ‘slime monster’ traces back to D&D. The ochre jelly, mustard slime, gelatinous cube and so on were a bit closer to traps or dungeon features than actual monsters (the idea being that wouldn’t notice them, and would walk face-first into the transparent cube of acidic slime), but they’re still the originator here.

As you can see, there were a couple changes made. I’d like to thank D&D second edition for having art of the Gelatinous Cube without bones in it, so I can actually post it here.

Some of it came through the channel of western video games. The Wizardry series is basically a time capsule of the old ‘just march through a dungeon, take everything that’s not nailed down and probably die a lot’ era of D&D, right down to taking sudden, extremely confusing detours into science fiction. Oh, and the part where In the west, Wizardry died out with the 8 th game in 2011. In Japan, the series became so wildly popular that it’s still going to this day, and nostalgia for it has created the Etrian Odyssey series, followed by a small but ongoing resurgence for that type of game on handhelds.

An argument could be made for the more modern Dark Souls series borrowing from this as well, with its very, very pointedly western approach to fantasy, and preserving some extremely Vancian approaches to magic, such as having a certain amount of slots to prepare spells into, and recovering them only when you rest.It’s a bit less obvious, but I think there’s some lingering influence there.

The Shin Megami Tensei series bears mentioning here, for being an odd little island. Without going into too much detail (yes, I know, it’s much too late for that), it frames most of the conflict in its series not as being between good and evil, but law and chaos: Two extremes where neither is at all human. This isn’t actually its invention, but borrowed from the very earliest editions of Dungeons & Dragons, which in turn took it from 70s pulp novels (most often those in the ‘weird fiction’ subgenre). Now that D&D has completely moved on to more conventional models, Shin Megami Tensei is left behind as an odd little island and the only surviving example of what it originally copied./p>

By far the strangest example of this, though, is the Mana series. Secret of Mana in particular, but equally its sequel, which never actually got an English title or localisation, leaving people awkwardly calling it Seiken Densetsu 3. This, too, had some tabletop RPG enthusiasts behind it, but not D&D. No, instead, they drew from Runequest, which was never a direct competitor at the best of times, and barely exists today. More broadly, their playbook borrowed from Glorantha, the setting of both Runequest (the tabletop RPG) and King of Dragon Pass (a boardgame, and now a PC game of the same name). Glorantha, being a very strange bronze age fantasy setting, wasn’t much like the fairly Tolkien-esque (to the point that elves and dwarves were classes) assumptions of D&D.

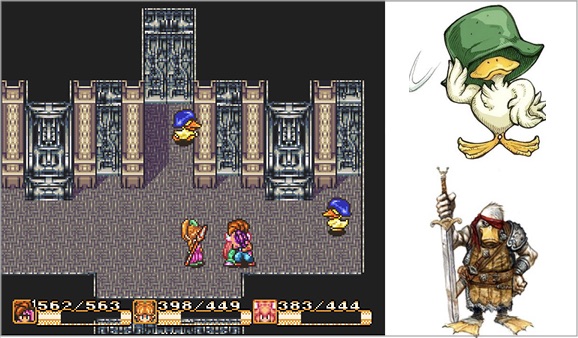

Runequest pioneered one of the earliest systems of your character getting better at something by doing it. With magic in particular, you could never improve unless you used magic regularly. In Runequest, this is complicated by the thousand and one risks of using magic; not so much in Secret of Mana, but you’ve still got to use each element of magic, and often, to improve.Runes don’t make much of an appearance here, but certain other things do, and I still can’t tell if the developers loved Glorantha that much, or just assumed everything in it was a staple of western fantasy. For example, the Mana series features monsters somewhere between a lizard, a human and an actual dragon, called Dragonewts: Something entirely original to Glorantha that appears nowhere else, and more stark than Final Fantasy’s borrowing for how much more obscure it is.

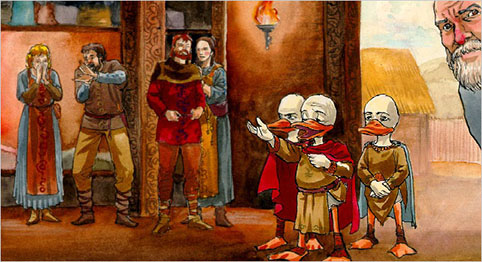

And then you have the ducks.

Ducks were born when Glorantha’s authors felt the need to include something like hobbits (or halflings), but also really didn’t want to. The natural next choice (which I’m sure any of us would do next) was to make a species of humanoid ducks. Then, because the artist didn’t really know how to draw ducks, he traced over pictures of Donald Duck. Then, since Glorantha was awfully invested in being a dark and serious setting, he made the ducks into angry crossbow-toting cultists that live in swamps.

I know how this looks, so I want to emphasise as much as I can that this is actually what happened, and not a joke. Next to the evidence of things like dragonewts, you start to understand where all the ducks came from.

To this day, I keep hoping that the developers of the Mana series had just completely misunderstood what the basic pillars of western fantasy are, because it would be much funnier.

But to take a break from borrowing, what came through the other way, from Japan into tabletop games? That gets a bit hard to quantify, especially if you look specifically for games that borrowed from tabletop, and gave something back to it later in their life. Still, let’s try.

For brevity’s sake (I know it’s a bit late for that), we’re going to gloss over the various western productions that just reference Japanese culture or pop culture. There are so many of those, we would never get anywhere else. Let’s look at what else we have, though, that brought this full circle.

The JRPG style has inspired tabletop games trying to mimic its style and aesthetics; there are a couple examples, but Anima Prime may be one of the bigger ones. More directly, though not official, there are multiple Final Fantasy tabletop RPGs. Various Japanese games are cited as major inspirations for tabletop systems, such as Nobilis (though that’s a very odd game).

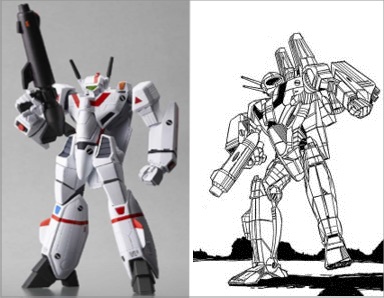

The entire existence of the giant robot (or ’mecha’ depending on who you ask) genre in Japanese media has inspired multiple tabletop RPGs (Lancer is a recent favourite), and spread into wargames as well, most famously Battletech (which borrowed enough from the Robotech series, a spinoff of the Macross anime series, that… let’s just say they had to redo a lot of their art for later editions), which has since been turned into about a dozen video games. The cycle goes around and around.

In all this, a few home-grown Japanese tabletop titles are making their way into the west too. Not many have been translated, but those that have tend to bring something very new to the medium: Ryuutama and Tenra Bansho Zero have both been described as a sort of fantasy road trip, while Golden Sky Stories is a rare tabletop RPG that doesn’t involve combat at all (for an idea of how rare this is, think about how often this happens in RPGs for video games; it’s about the same) and Double Cross is often described as a hybrid of Persona and Prototype. Localisation is difficult, so it’s been a slow trickle so far, but little by little, the results of this little cultural exchange are making their way back around.

Since this is a history lesson on hobbies, I can’t really say it’ll be much use, but it does put things in context a little more, doesn’t it? Next time you see something in an RPG, you might know where it first came from; a lot of this is such a normal part of video games by now that you might actually know more about where it started than the person who made the game!