Welcome back to The Case for the Kominka. In this part, we’ll be going further into the many distinguishing features of old-fashioned Japanese houses, starting with some of their unique rooms.

The main examples of such things are the Doma and Irori, or entrance and firepit. The former is a sort of half-and-half space between being counted as outside and as part of the house: It’s an entry hall for storing things, taking your shoes off or putting them back on when entering or leaving the house, and so on. Once upon a time, it was where you would keep, say, a horse in the winter. Doma means ‘earthen hall’ since they used to have earthen flooring, but these days it’s usually concrete.

The firepit, on the other hand, is a staple of old-fashioned Japanese life; a pit of warm coals that you can cook over (usually with a rope and hook hanging from the ceiling, which you would hang a pot on, but you can use it like a small barbecue as well), boil tea, or just sit around to warm yourself. These days we have better ways to cook and to warm the house, but it can still be nice, and it looks beautiful too: An example from mine is above.

These old houses sprawl, and every room connects to so many others. Get used to not seeing many walls outright; not when those walls can be turned into shelves or doors into other rooms, sometimes doors hiding staircases. Any Kominka will have many floors, and a maze-like sprawl of rooms leading into others. It takes some getting used to, but it means you can more or less go in a straight line between any rooms in the house, which is nice.

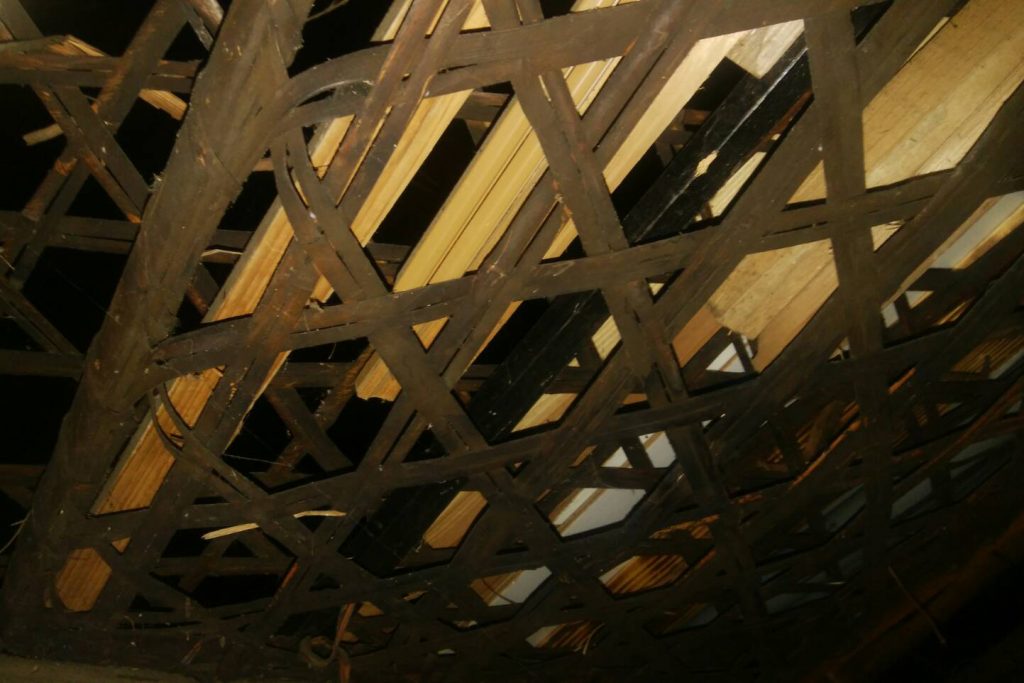

Kominka are, of course, old. Don’t take that as a sign of fragility, though. Lasting for so long is, if anything, a show of how sturdy these houses are! They do show their age in some ways, though. You can find many signs of the people who lived in the house before you, and their lives; for example, this house is full of silkworm racks from who knows how long ago. Many of them have been repurposed as decorations since, but here are a few that haven’t.

Another example is the soot, and no, I don’t mean that in a bad way; years of firepit use have stained a lot of the wood a beautiful dark colour, to the point that when I had to replace some of the doors, I seared the wood so it would be the same colour. It does mean the house can be a bit dark, though; don’t be afraid to break out big lights and white paint where you want to!

At the time they were built, these houses had to think a bit about priorities, and they chose comfort in summer over winter, in a sense. The idea was that good ventilation would make summer heat easier to bear (in a time before electric fans or AC), and in winter, everyone could cluster around points of heat (heated tables, wood stoves, the firepit) without any plans to move very far. It might not be the balance you want, but it’s nothing you can’t solve with insulation or more vigorous heating.

Of course, there’s the extra space too. If you want, you can use the hollow space inside the roof as anything from a storage space to a home theatre (it’s probably worth mentioning that each of these houses has at least a few rooms with extremely high ceilings, think 10 metres/32 feet in the bigger cases, which you can do a lot with!). Beyond that, there’s usually a fair bit of land around the house that can make a nice garden, complete with a few trees, at least some of which are probably fruit trees (persimmon and chestnut in particular are very popular, and you might well have one already!)

The standard for floors in modern Japanese houses is linoleum, carpet or sometimes wood. For a Kominka, expect a combination of wood and straw mats (easily replaced, smells nice, and keeps warmth better than wood, but a bit hard to clean stains out of sometimes). The good news is that with a bit of work you can pick whichever you want, room by room; there are even thin straw mats you can unroll and lay down over any other floor. Doors, meanwhile, are all sliding shoji doors: A wooden frame in the middle of the door that gets papered over for covering. This is easily replaced if it gets torn, but if that’s too much, you can bolt on some clear plastic. Speaking from experience, this one really has to be done if you have several cats.

Now that you have an idea of some of the quirks of Kominka, join me next time, where I explain exactly what these houses have to recommend them.