In many ways, where the internet is concerned, Japan is an unusual country — not least because its adoption of the internet on a wider scale was relatively late, given the rarity (until quite recently) of home PC use. To this day, online activity maintains a phones-first attitude (and sometimes consoles, when it comes up). Gaming online is, even leaving phones aside entirely (which I will, because mine only exists to play music and call people), also quite different from what you might be used to. Don’t worry, though, it’s mostly good news! All the same, it pays to know what to expect. My perspective on this is a PC player, but a great deal of it if not all should apply to consoles as well.

Let’s start with speed. The Internet in Japan is fast, and for most of the country, quite reliable. As far as I know, Korea is the only country in the same league at all. Download and upload speeds will be quite fast. Actual ping while playing, on the other hand… well, it’s complicated.

For a start, a lot of online games assume that you’re in the US, or somewhere in Europe. Japan is quite far from either. Quality of internet is the only reason playing on US and European servers will net me 100 to 200 ms ping, rather than something far worse. I don’t mind it, but a lot of people do. In particular, if you moved here from somewhere very far away and want to play with people from back home, this could be a problem. So could time zones if you want to play at the same time as someone in particular (assuming you ever sleep at sensible times — I don’t — or make sure in advance that all your friends are Australian).

There’s also the matter of netcode. The short version is that there are two ways to go about it. One uses a pre-established server everyone signs into, like what MMORPGs do (to take one of many examples). This is just going to depend on where the server is; see above, but if the language barrier isn’t an issue, lots of online games are starting to roll out servers in Japan, Singapore or Korea recently, all of which are quite a bit quicker than the alternatives.

The other model is peer-to-peer. One player sets themselves up as the server, the other connects, and you go from there. This is probably going to lag badly for whoever’s not hosting, but it honestly changes a lot for me between different people in the same country, and even different days; you’ll just have to try. This mostly comes up for fighting games, one of Japan’s bigger genres for online play. Unfortunately, most fighting games have dreadful netcode. In particular, independent ones are more or less built on the assumption that you would never play them with someone outside the country, with predictable results when you try to play against someone on the other side of the world. It’s not a dealbreaker but it could be a lot better. Luckily, most other online Japanese games in English don’t have this problem; they use centralised servers like everybody else.

Peer-to-peer games in general might require port-forwarding: This isn’t strictly about Japan, but if you have difficulty with accessing your router, I recommend Hamachi and equivalent programs to fake a LAN connection, which is the next best thing.

For everything else, on the other hand, you can bet on reliability and speed throughout. That is, unless you use wi-fi. Please don’t use wi-fi, you deserve better than that.

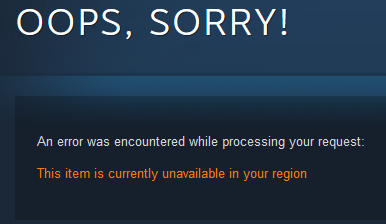

Next, there’s buying the games themselves. Regional markups are infamous in gaming, and Japan is no exception, but it does better than most. The asking price digitally is usually a bit more than the US, but less than most of Europe, and much less than Australia or New Zealand. This is, I promise you, still cheaper than buying a physical copy new in Japan. The other issue is region-locking. Quite a few games are not available digitally in Japan; in the past, this used to be because publishers overseas thought selling to Japan would lead to piracy (I still have no idea why they think this). These days, it’s mostly on games made in Japan, to make sure potential customers buy the localised Japanese version when it comes out a few months later, or possibly a physical copy; in short, whatever costs most. It’s not ideal, but you learn to deal with it.

Another potential issue is chat. Even if chat is compatible with Japanese characters (not a given), typing a message in IME is always going to take significantly longer. Between that and consoles, you might understand why so many Japan-made online games rely on preset messages.

Finally, let’s pivot around to some good news again. For reasons that would take far too much talk about culture and internet history to explain properly, the Japanese internet is pretty different from much of the world in culture. Which is to say, it trends towards being more polite and friendly (and more formal for a while, but Twitter seems to have mostly put a stop to that). It’s not absolute, of course, and there are some pockets that you don’t want to go to, some of which are entire games (let’s be honest with ourselves, nothing was ever going to salvage some online gaming communities; looking at you, League of Legends), but by and large it’s a far more positive and pleasant experience. I can’t speak for anyone else, but it does a world of good for my mood and general burnout while playing. It’s also usually more businesslike than chatty, admittedly: People say something at the start of a round and maybe at the end, keep a few preset messages handy and then largely keep quiet. Still, it’s a huge improvement and I’ve yet to really run into any trouble, which I appreciate a great deal.

Now that I think of it, every game I ever bought with an online component has had several pages in the manual about online etiquette. I have to wonder how much of a difference that made.

So, there you have it. Speedy, reliable, and friendly: If there’s an issue with Japan’s online gaming at all, it’s that you’re in Japan while much of the world obviously isn’t. Other than that, it’s a very nice deal.